By Iván Cachanosky

October 2011, the government of President Cristina Kirchner created a “clamp” on the exchange rate, establishing a maximum rate with the objective of slowing the escape of foreign currency reserves from Argentina. However, the result wasn’t as hoped — reserves ended up dwindling at a rapid rate, with the impact being felt in other variables of the economy, from the balance of trade to the foreign-exchange market.

When analyzing the situation of foreign reserves that the current president presides over, we should first note that this figure stood at around US$40 billion in May 2007.

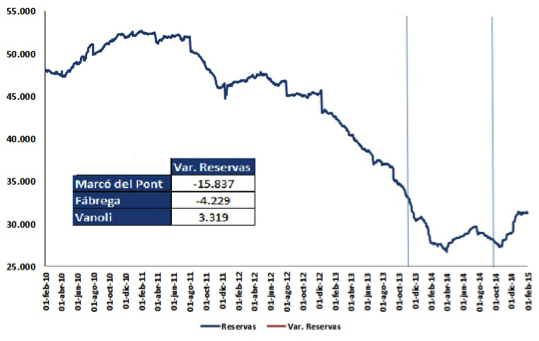

Reserves began to increase, reaching a peak of over $52 billion in February 2011. But the government subsequently began to lose its hard-gathered cash: in October of that year, the level of reserves was at $47 billion. The loss of some $5 billion in seven months prompted the government to hastily install the “clamp.” From then on, the Central Bank was managed by Mercedes Marcó del Pont.

Yet reserves continued to tumble. On November 18, 2013, they amounted to barely over $32 billion, and Marcó del Pont was unceremoniously ejected from his post.

His replacement was Juan Carlos Fábrega, with a prestigious career at Banco Nación behind him. However, Fábrega himself lasted less than a year, exiting through the revolving door on October 1, 2014, with reserves at less than $30 billion. His shoes were filled by current Central Bank President Alejandro Vanoli, who has proved to be more in line with the ideas and political policies of Economy Minister Axel Kicillof.

To date, Vanoli has managed to largely halt the flight of reserves, which now stand at $31.3 billion. This slight increase has been hailed by the government as a victory. But the marginal uptick has been achieved through dressing up the numbers, rather than a genuine boost to reserves.

Firstly, the implementation of the “Chinese swap“ doesn’t mean a real inflow of the needed currency: it’s not dollars entering the country, but yuan. While this permits some dollar savings, the ideal situation would be securing dollars by incentivizing them to enter the country, rather than having to negotiate with a third party. To date, the dollar value of the imported yuan is $3.1 billion.

Furthermore, there are other issues to bear in mind: an advance of dollars granted to agricultural producers in January (worth $1.5 billion) and external debt for imports already carried out ($5 billion). The “increase” in reserves is clearly nothing of the kind, and is the result of playing with the numbers rather than the influx of dollars. If we add to these figures the deposit accounts that private banks hold with the Central Bank, the level of liquid reserves is only around $11 billion.

It’s worth stating that this last figure is very debatable. Perhaps it wouldn’t have entered into public discussion if reserves were more robust, but as external assets are melting away, these private accounts are now entering into the picture, even though they’re not freely available to the government.

International Reserves

Levels of reserves in millions of USD, according to Central Bank figures.

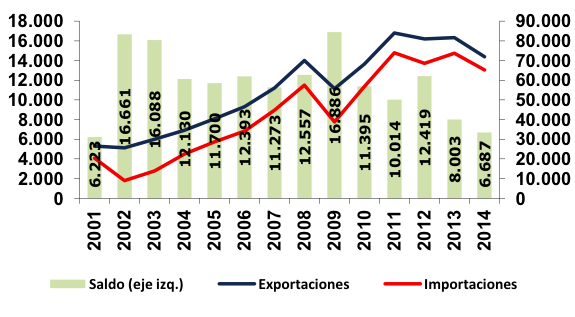

On the other hand, the balance of trade is also in jeopardy. The previous year saw the least surplus generated in the entire Kirchner period, the result of controls on imports. The reason is simple: restricting imports also risks exports, because imported goods are necessary for the domestic manufacture of products which are later exported.

For this reason, both imports and exports began to fall with the implementation of the clamp, risking the balance of trade, as can be seen below. Furthermore, it must be highlighted that the most important cause of exports falling is the retention of one-third of the export value implied by this fixed exchange rate, while the real value of the peso remains one-third lower.

Balance of Trade

Imports/exports in millions of USD, National Institute of Statistics (INDEC) figures.

With regard to the foreign-exchange market, both the worth of the official dollar as well as the street rate are on the rise, principally a result of the devaluation of the local currency. The official peso, meanwhile has been devalued by 104.5 percent since the installation of controls, while the parallel has fallen by 189.7 percent in the same period.

In conclusion, the installation of the exchange controls had as its principal objective halting the fall in reserves. It was a complete failure: since their creation, reserves have fallen by $16.2 billion to date. The inefficiency of the policy has cost two Central Bank presidents their jobs.

Added to this, 2014 saw the worst trade surplus yet of the entire Kirchner administration. And finally, the foreign-exchange market continues to plummet, and people continue to place their trust in foreign currencies over the peso, suffering from elevated inflation (38.4 percent year-on-year in 2014). These are more than enough reasons to scrap this damaging and ill-thought-out measure.

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: In Argentina, Significant Investment Lies In The Balance Of October’s Elections | EMerging Equity - June 20, 2015